Read The Code (Sometimes)

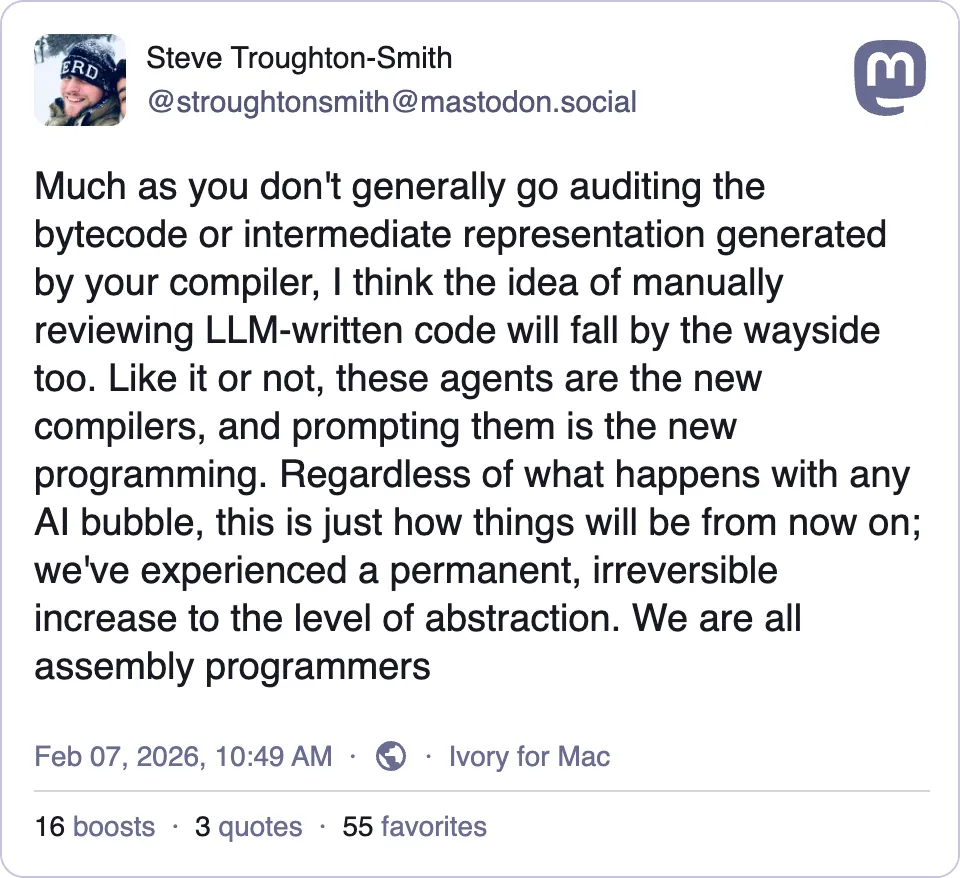

This weekend there was once again a debate about the future of programming, stemming from this comment by a longtime developer Steven Troughton-Smith. Steven has just gotten into using AI for programming, and as a result he is discovering just how powerful it is.

- Steven Troughton-Smith on Mastodon

There are a lot of people who haven’t invested much in using agentic systems to write code, for many perfectly good reasons. And often, they haven’t updated their understanding of how LLMs work, still calling them “random word predictors” or “stochastic parrots” — without considering how much more complex agentic systems like Claude Code or Codex have become. As a result, there’s often a lot of debate (particularly on Mastodon) built on false premises or misunderstandings about how LLMs work.

Then there are sensible people like Manton Reece who are not just looking to prove their worldview is right. Manton wrote a blog post titled Read The Code that I mostly approve of, but also subtly disagree with. The premise is that you still need to read the code that agentic coding tools output. I follow this rule when it comes to the Plinky — a piece of software I derive my livelihood from — but I want to share a story that directionally agrees with Steven. As programming becomes more abstracted, what matters most is not whether you can read the code, but whether you understand the problem you’re solving. Domain expertise — not code literacy — is becoming the real differentiator.

Building A Financial Model

Last night, I saw this play out firsthand. My wife Colleen and I built an app to create a visual representation for when we can retire. We spent 20 minutes writing a prompt that codified our goals and circumstances, and Claude generated a tool that let us visualize our financial options. I wanted to see what our future would look like if I stayed indie, or if I went back to work full-time for 2, 5, 7, or 10 years. We added variables like cost of living, the percentage of real GDP growth, whether we’d have a family, and a few other factors relevant to our personal life.

We asked Claude to ask us some more questions to fill in any gaps for the things we didn’t consider, and spent about 10 minutes answering those follow ups. We went through a few iterations because we had to tweak scenarios and variables — all done through prompting. At some point Colleen noticed we could never retire earlier than 2040 no matter what we changed — even if we simulated ourselves winning the lottery. Many programmers would say “this is proof an LLM can’t do math,” but it’s just code under the hood. The real problem is that most people would have accepted the incorrect output and made important life decisions based on flawed software.

But Colleen doesn’t know how to code, and instead she suggested we ask the model in plain English what assumptions it had baked in. It listed 15 assumptions, and one was “I assumed you wouldn’t want to retire before 2040.” We both exclaimed “wait, why?” — and Colleen joked that the model wants us to keep working so we can afford more tokens.

Rather than scrapping the project, we cleaned up the assumptions and kept testing until the results matched our intuitions. It was more than intuition though — we had a few known outcomes — unit tests by another name. You know what we never did though? Look at the code. The more important factor was working through this with someone who has financial modeling experience, because we could validate our assumptions and outputs in other ways.

Not Quite Assembly, But Close

It was effectively assembly to us. With no programming experience, Colleen couldn’t have understood what it was doing, so it definitely was assembly to her. But she didn’t really need to. What mattered most was that she could validate the outputs, ask the right questions, and catch the flawed assumptions baked into our financial model. In this case — and in many cases — having domain expertise is more powerful than being able to write code.

This is why I think Steven is more directionally correct than Manton, even though I still will often read the code. Not because all software will be built this way — I certainly don’t want to fly in a plane powered by software built with intuition. At the same time a reasonable amount of software will be built this way, with little or no detriment to users. Software is not just random code — it’s intuition and experience codified into syntax.

When I work with non-technical students at Pursuit or in my workshops I’ll often get questions about what they can do without knowing how to code. Some have huge ambitions so I tell them that vibe coding won’t help them build the next Google, but it will let them build software that solves real problems they have. And if you have the right foundation of knowledge, you won’t even need to look at the code.